|

|

|

|

NOWHERE STORIES The basic technical principle was to misuse a program/technique that was designed to build panoramic movies out of a series of compatible photos (about 10-12 images per panorama) in order to rebuild the original scene as a panoramic view. We fed the program with countless stills taken from videotapes of movies to see how the program works with finding a way to stitch together images that aren´t compatible ...

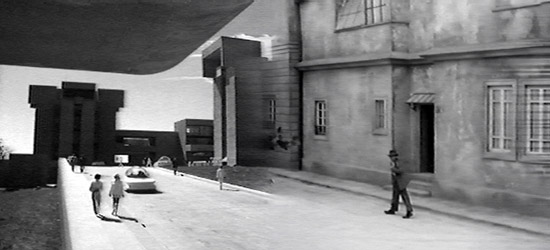

WHERE IS NOWHERE? How define something that, by human logic, defies verbalisation just as much as it does visualisation; something that is just as impenetrable to our thoughts as infinity? There is an obvious solution: Let us try to define the outlines of the problem by pinning down what it is not. So: Nowhere is the opposite of everywhere. Whatever is not comprised in everywhere cannot be at all. No room for outlines. Nowhere does not exist. Which is what Candela2 did. The resulting "Nowhere Stories" are accessible both as an installation of clearly defined location (and, hence, an intriguing paradox of work and title), and on the Internet, on a server that is said to be located in Kassel. What it feels like when these reference points which help define our existence are momentarily beyond our reach is probably best exemplified by that oddly drifting sensation we experience some mornings, during that semi-conscious dawning of thought we most strongly perceive when not having been abruptly torn from sleep by the dictatorial scream of a pre-set alarm clock but woken up all by ourselves. Gradually fading impressions of dreams with their sudden changes of scene melt into first sensual impressions of the "real" world. At this stage there is a brief moment when conscious thought and feeling have already begun to emerge yet the questions "Where am I?" and "Good grief - what time is it?" are still left unasked. For a moment we enter Nowhere - no matter where we (respectively our bodies) are physically. Leaving Nowhere frequently goes along with surprise, or even shock. This is even more so when we wake up someplace else than we usually do - when travelling, for instance. C2 reconstruct the time- and placeless moment between dreaming and being awake as well as the irritations that often follow directly afterwards by a multi-dimensional computer collage of linked panoramas. Using "Quicktime VR", viewers can zoom in and out of them and move their viewing angle by 360 degrees. The protagonists of "Nowhere Stories" are buildings, not men or women. Granted, there are, in almost each of the panoramas, people appearing. They seem, however, strangely lost in these anonymous city landscapes that have been consciously deprived of locatability: Images of fictional (Metropolis) and actually extant places (Vienna, post-war Berlin, Egypt) are seamlessly blended into each other: a tunnel. Ruins. A child playing. A Ferris wheel. Pillars. The Sphinx. In spite of the obvious difference to the everyday world, our instruments of orientation remain active, ceaselessly seeking matches with the familiar. Occasionally, they succeed. Here, a man: James Steward, as it seems. There, a castle reminding on Citizen Kane´s "Xanadu". A few clicks and turns further, a sign: "Las Vegas" - a misleading suggestion of place. Taken out of its context it becomes strikingly obvious that it might just as well have been put up in some potato field in Iowa by the four women in the foreground. Most of the time, though, the conventions by which we normally make sense of what we see fail, and we struggle to build new ones. A large part of the reason for this failure lies in the smooth transitions combining the movie stills, suggesting to our eyes a consistency that our mind says is not there. Film reception has made us grow accustomed to filling in narrative gaps by mentally reconstructing what must have occurred during a given cut (a journey, changing clothes, ageing...) to lead up to what we are seeing at present. In "Nowhere Stories", however, this process of mentally filling the gaps during which our imagination manages to make up for several years´ worth of action in a few milliseconds is taken over from us - intriguingly by a machine which, of course, could not care less about such human categories as a consistent notion of space and time. All the computer looks for are optical similarities; bit patterns the images selected by C2 have in common. It comes up with combinations our rational or intuitive criteria of choice would often not have thought possible - to frequently striking effect. Having faced Nowhere for a while, one cannot help but wonder whether we really are where we believe to be, whether, right and left of the narrow field of vision framed by the window, there really is nothing but the continuation of the familiar road behind the house, and, finally, what really constitutes a place. And suddenly we get an idea where to find Nowhere: Nowhere is everywhere.

|